“In any field, find the strangest thing and explore it.”

Hal Rammel

Views Through a Kaleidophone

The gray concretions and rebar scoliosis of modernity cast a long shadow. Yet within its shade rest copses of organic wonder and moments of brazenly murmured splendor. Tracing the Wisconsin backwoods, Hal Rammel quietly thrives beneath the diffident gusts of commerce. As a self-publishing artist, inventor, composer, writer, and photographer, Rammel is a polymath of the highest order. A 60-year body of work situates comfortably alongside that of Harry Partch, Harry Bertoia, and Harry Everett Smith, smearing the boundaries between science and art, craft and cosmology. From homebuilt instruments to stereoscopic imagery, confabulated folkways to whimsical illustrations, his peripatetic footpath crosses the dreamlike and the empirical, the sonic and the seen. A natural philosopher, Rammel is persistently attentive to the twinkling that beckons in the dusk of perception. His efforts are not declarations. They are demonstrations: bouquets of radical, radiant poetics.

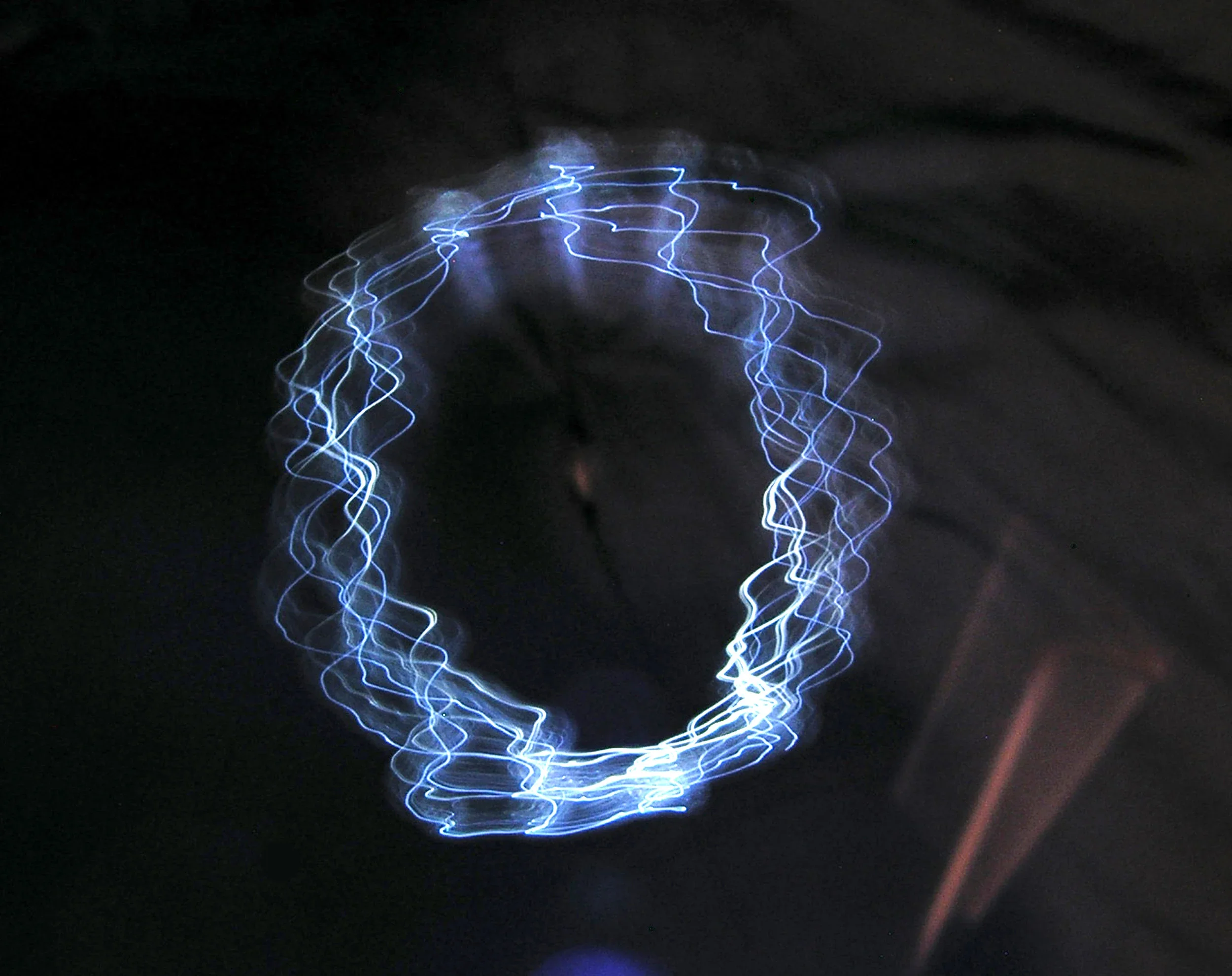

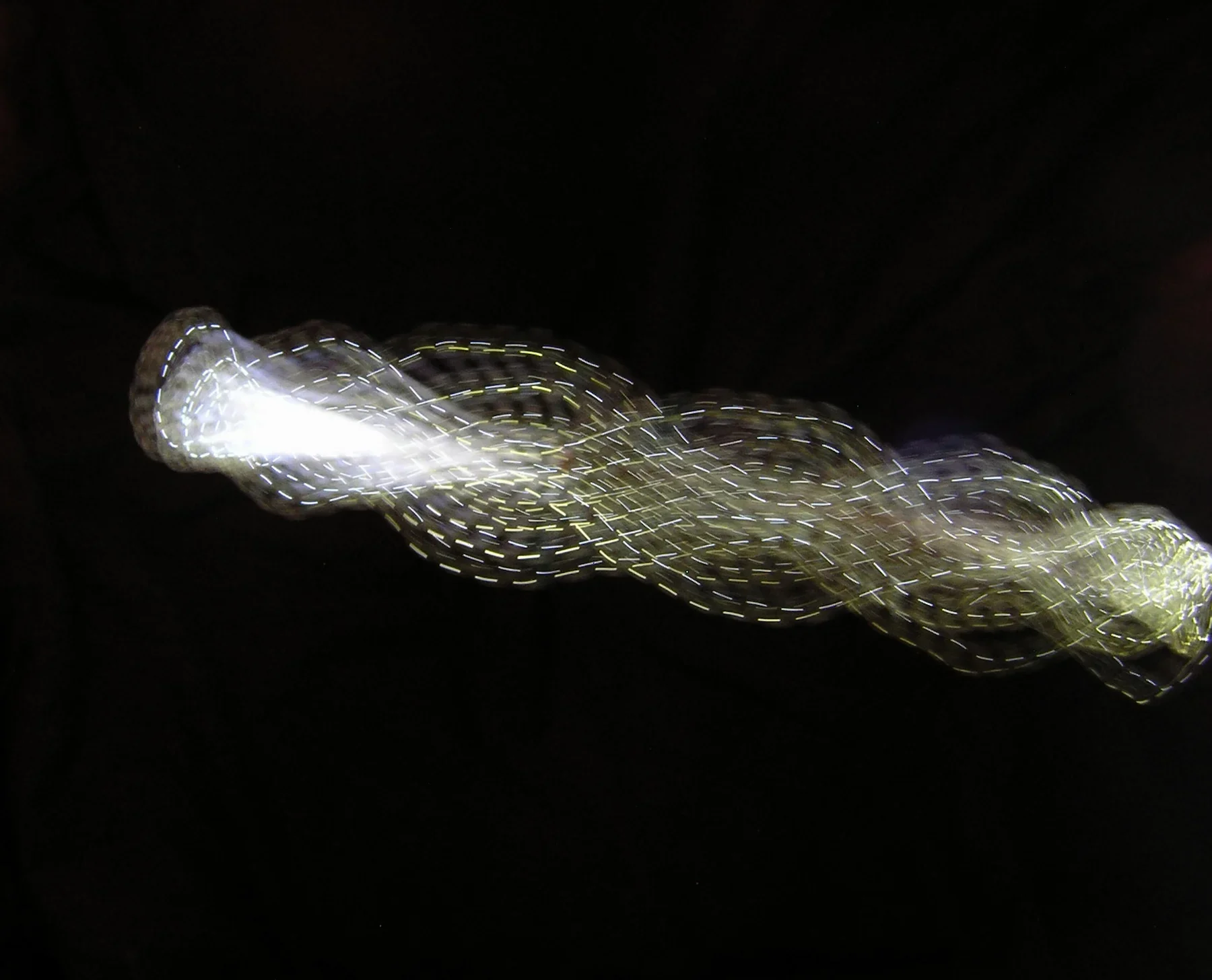

One demonstration begins with an obscure instrument from the dawn of modern science. In 1827, British physicist Charles Wheatstone devised the kaleidophone, a “philosophical toy” built to visualize vibration. A slender rod of metal, tipped with a bead, was fixed to a wooden base and bowed or struck to produce an oscillating motion. With a light source directed at the bead, these vibrations became visible as continuous lines tracing elliptical or spiral paths through the air—early graphic evidence of complex harmonic motion. Though Wheatstone is best remembered for the stereoscope, concertina, and, prominently, the electric telegraph, the kaleidophone reveals a more profound preoccupation: that sound, light, and movement might be coaxed into shared expression. It was never a musical instrument in the conventional sense—but it was played, and it froliced in response.

Utilizing the same fastidious verve that he applies to his invented musical instruments, Hal Rammel has recreated Wheatstone’s kaleidophone. Photographing the device under LED light at varying shutter speeds, he captures luminous patterns that the eye could never retain alone. The results are arresting: fluid ellipses, torqued spirals, and flickering geometries that hover between waveform and calligraphy. These images are not illustrations of motion—they are motion, frozen mid-gesture. Each photograph documents not a static object but an event: a performance composed of strike, light, timing, and the unpredictable grace of vibration itself. In setting the device in motion—striking, bowing, coaxing—the artist captures luminous, swirling geometries that seem to dance in space.

These images, taken at varying shutter speeds, vividly animate the ephemeral beauty of vibration, transforming a scientific curiosity into a living sculpture of light and motion. Rammel’s photographs burst with hypnotic energy, inviting us into an active engagement—a momentary performance frozen in time, where light, sound, and perception converge in a hypnotic dialogue. In this act of revival, Rammel celebrates the playful inheritance of science as art, reminding us that the unseen energies of the universe can be both mesmerizing and deeply poetic.

• • • • •

“Liberation from the prescribed or predetermined visions of mass-marketed instrumentation and the top-down designations of traditional pedagogical art processes is the key to Rammel’s creative arc. Whether engaging in cartooning collage, sculpture, improvisation, instrument building, photography, or countless other arts, his drive is toward an exploration of what’s left out of the commercialized experience and a subsequent, subtle rereading of the high versus low art divide.”

— Jon Dale, TheWire

“The unearthly improvisations of instrument inventor Hal Rammel are never predictable: whether he’s bowing a saw or running his electroacoustic sound palette –- a sensitively miked painter’s palette intersected by variously long wooden dowels –- through a gamut of space-age effects, both the sounds he generates and the directions in which he takes them are often surprising.”

— Peter Margasak, Chicago Reader

“Something about Hal Rammel's instruments — their design and materials, the sound they make, and his relationship to discovering the music within them — embodies the patience and acceptance of a loving father and his daughter or son. With Rammel, you get a sense that the construction of each of his instruments is secondary to discovering who it will become as it matures.”

— Nate Wooley, Sound American

“Words only paint a flat picture of an artist like Hal.”

— Nate Wooley, Sound American

”Rammel is a wonder unto himself. “

— Peter Margasak, Chicago Reader